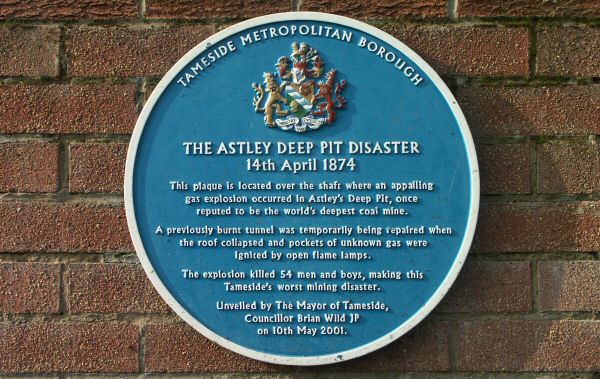

THE ASTLEY DEEP PIT DISASTER

This plaque is located over the shaft where an appalling

A previously burnt tunnel was temporarily being repaired when

The explosion killed 54 men and boys, making this

Unveiled by The Mayor of Tameside,

14th April 1874

gas explosion occurred in Astley's Deep Pit, once

reputed to be the world's deepest coal mine.

the roof collapsed and pockets of unknown gas were

ignited by open flame lamps.

Tameside's worst mining disaster.

Councillor Brian Wild JP

on 10th May 2001.

The plaque stands in the centre of a pleasant circle of houses at the end of a quite cul-de-sac.

A hundred and fifty years ago this place was very different. Noisy, dusty, and dark with smoke. It is difficult to imagine the contrast. Here, men and boys made the ear popping descent down a pit shaft to spend long hours toiling in the bowels of the earth. Some didn't return alive. The blue plaque is their memorial.

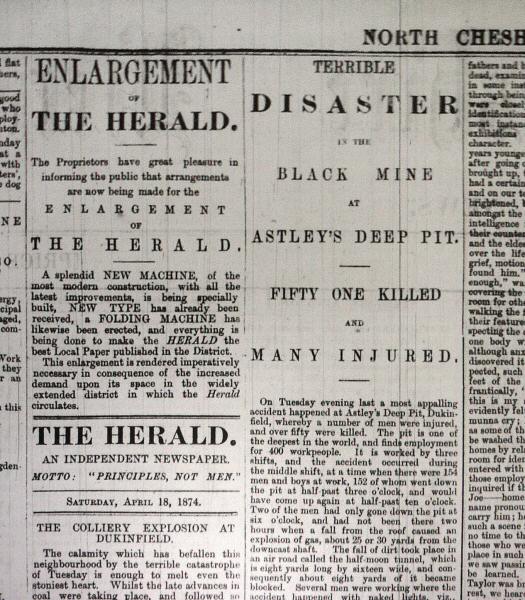

At about eight on Tuesday evening, a length of the roof fell with a loud crash, blocking the tunnel some 25 yards from the main shaft. The repair team heeded warnings and jumped aside. No one was hurt by the fall. But the fall released gas which had accumulated in a cavity. This was ignited by an open flame. The resulting explosion extinguished the lights, and started a fire which took hold in wooden structures further down the tunnel. It was particularly strong by the stables and near the furnace.

George HARRISON was working nearby and had been talking to the repair team at the time of the fall. He was blown a few yards by the explosion, but soon recovered. In the darkness he made his way out, on the way collecting three boys Henry FIELDING, Joseph FLETCHER, and David CHADWICK. They found the main shaft still in working order, rang for the pit cage, and were hauled to the surface to give the alarm.

Rescue work began with two pit underlookers, David HOLMES and Abraham ELSE, together with George HARRISON and Elijah SWANN being slowly lowered down the pit shaft, checking for bad air as they went. At the bottom they started to explore the passages. They were soon joined by James HILTON, the pit manager, who had remained on the surface a short while to organise help.

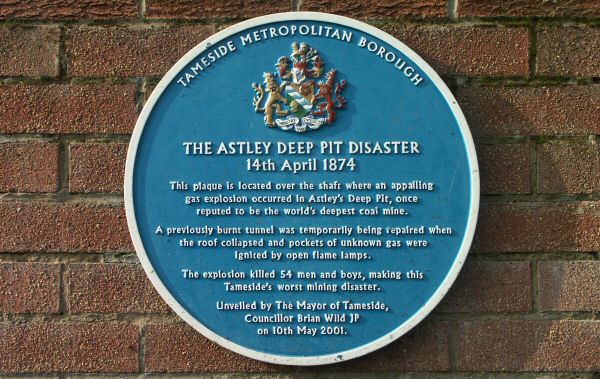

Throughout the night teams of volunteers descended the pit in relays, working to fight the fire, open passages, improve ventilation, and support the roof. Assistance was received from local pits and mills, and from Ashton-under-Lyne, Hyde, and Denton fire services and police forces. A large crowd gathered around the pit head. It could see dense smoke billowing from the upcast shaft.

HARRISON had been on the right side of the roof fall. He had been able to escape. Ninety miners working in another part of the mine were soon evacuated. But the roof repair team, and sixty others working at the far end of Half Moon Tunnel were not so lucky. They were imprisoned on the wrong side of the fall, being threatened by fire and fumes.

A number of men tried to escape by passing through the heat near the furnace. Of these, three made it to the exit. John SWINDELLS and Albert BOWKER both later died of their burns. James BUTTERWORTH survived, but he had started before the fire really took hold.

At five on Wednesday morning, ten men were found alive in Cannel Tunnel. Joseph NORMANTON, George DEAN, Jack WALKER, William KELLETT, Thomas HITCHIN, John LEES, Thomas WOOD, Allen HULME, Charles HULME, and Samuel CLAYTON. When the explosion occurred they had initially moved away from the pit shaft, thus avoiding the foul air that suffocated others. They then made their way via old, little used, passages to a different part of the pit.

From then only bodies were found. By eight on Wednesday evening, most of the bodies had been recovered, but the fire was still raging. Rescuers felt that no more could be done until the fire was under control. Firemen struggled throughout Thursday. It was necessary to get close to the fire. At first the teams of four could work for only fifteen minutes before needing to be relieved. It was not until two on Friday morning that the fire was extinguished, and two in the afternoon before the last of the bodies was recovered. The last was Charles JONES who had entered the pit on Wednesday as part of a rescue team. He had been overcome by fumes while searching a remote part of the pit.

Above ground, teams worked to wash, dress, and identify the bodies. Some were badly mutilated. It was several days before the last was identified.

In later times when people commuted further the effects would have been more widespread, but these miners walked to work. A lot of anguish was concentrated in a small area. Those who died were:

The injured and survivors of imprisonment:

Edward DAVIES's coffin was carried through the streets of Ashton-under-Lyne on the shoulders of fellow Brethren of the Enniskillen Lodge of Loyal Orangemen, a Lodge which usually met at the Brunswick Hotel on Catherine Street, Ashton-under-Lyne.

Richard FLETCHER was escorted to his last resting place by Brethren of the Honest View Lodge of the Ancient Order of Shepherds. After the ceremony they returned to their usual meeting place, the Highland Laddie Inn, on Old St, Ashton-under-Lyne, to toast "the memory of the departed".

Law TAYLOR and Robert THOMAS were both volunteers with the 23rd Lancashire Rifles and were buried with full military honours. They lived close to each-other on Warf Street but were due to be buried at different locations. This presented a problem for Colonel MELLOR. There was only 90 minutes between the two burials, insufficient time to guarantee that the whole Battalion could attend both funerals, particularly bearing in mind the congestion expected at Dukinfield Cemetery. He decided to split his 250 men. D Company and the Regimental Band escorted Law TAYLOR at a slow-march uphill to the Cemetery, the band playing the "Dead March in Saul". After the ceremony, and firing three volleys over the grave, they marched briskly downhill, just in time to catch up with the remainder of the Battalion who had started to carry Robert THOMAS on their shoulders slowly towards Christ Church in Ashton. After the solemn ceremony, and the firing of volleys, the Battalion left the churchyard quietly, but according to The Reporter, the band then "struck up a lively air" as they marched back to the Drill Hall.

John GARSIDE had held a responsible position at Dunkirk Pit. He had only recently left there to work at Astley Deep Pit. He was held in very high regard by his fellow colliers. 120 of them from both pits, wearing sprigs of thyme in their button holes, accompanied the hearse carrying his and his son's bodies to St John's Church at Hurst.

Ambrose HYDE's coffin was escorted by 30 teachers and pupils from Dukinfield Independent Sunday School.

Nelson HARRISON's family were accompanied by a large number of his friends. His coffin being carried by fellow colliers.

Robert Ogden BRICE's funeral should have been conducted by the Reverend G T BARKER, but unfortunately due to a hitch in the arrangements he failed to attend. An impressive ceremony was conducted at very short notice by George TAYLOR, a Wesleyan preacher.

Dukinfield's relatively new Municipal Cemetery was busy all day. At one time two funeral parties (Robert DUGDALE and John JACKSON) both accompanied by large numbers of friends, arrived simultaneously to use the Dissenters Chapel. There were already two funeral parties (George LINDLEY, and William HARTSHORN) in the Church of England Chapel.

Sunday was even busier. Extra trains had been laid on to bring relatives from other towns. From early morning Dukinfield was a sea of people dressed in mourning. Groups of men, and some of women, from various clubs and societies marched purposefully to their late member's homes. Funeral corteges wove a slow stately choreography across the small town, from home, to church or chapel, thence to place of burial. Some corteges were small, just half a dozen colliers carrying a coffin on their shoulders, followed by the family and a gathering of friends and colleagues. Others were larger, perhaps headed by a band playing solemn music, a squad of members of some club or other, a hearse, carriages for the family, always followed on foot by a crowd of friends and colleagues. The town was packed. The police had trouble keeping the roads open. Sounds travelled a long way in the days before the motor car. Up on Chapel Hill, where the Municipal Cemetery and the Old Chapel burial ground lie side by side, solemn music could be heard coming from many directions.

On that day, according to The Reporter, no less than 26 bodies were laid to rest in Dukinfield Municipal Cemetery. Funerals followed one another in slow succession. Owners of hearses and coaches ran a shuttle service. As soon as a funeral party had been decanted, the hearse and coaches trotted off to pick up another.

John and Thomas KEAN were escorted to the cemetery by 200 members of the British United Order, who had assembled in their "Rural Cottage Lodge House" at The Painter's Arms, Old Street, Ashton. Wearing black scarves and black crepe, they then processed to the deceased's residence headed by the Moss Rose Reed Band. At the house they were joined by a contingent of teachers from Roman Catholic Sunday Schools wearing black scarves and green rosettes.

Some burials took place in Hyde where things were very different. Here the funeral corteges passed through almost deserted streets. Most of the inhabitants of the town had gone to Dukinfield for the day.

Joseph BICKERDYKE had been a member of the Rose of Allandale Lodge of the Order of Gardeners, normally held at the Astley Arms, Flowery Field. Members attended his funeral.

Nathaniel BICKERDYKE had been a member of Lodge 970 of the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds. Members assembled in their Lodge Room at The Hallbottom Gate Inn, Newton Moor, then marched to Newton Wood behind the Hyde Liberal Band. There they joined a contingent of teachers from St Mary's Sunday School, Newton, where Nathaniel had taught.

Thomas BROWN had been a member of the Foundation Stone Of Truth Lodge, held at the Freemasons Arms, High St, Stalybridge. The Brothers "accompanied his remains to the grave".

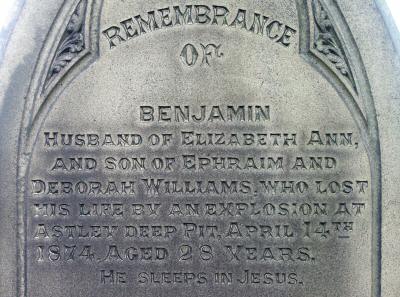

Benjamin WILLIAMS had been a preacher at Foundry Street Chapel. The large congregation attended his funeral.

John BAYLEY had attended the Bible Class at St Luke's Sunday School. Members of the class walked in front of his coffin.

James HALLAM had been a member of the Peace of the Valley Lodge of the National Order of Oddfellows, held at the Chapel House Inn, Dukinfield. On the way to the cemetery, members formed a procession in front of the coffin, with the family following behind.

On Monday it was the turn of Charles (The Explorer) JONES. He was the rescuer who had entered too far into the pit and been overcome by fumes. When they tried to bury him it was found that his grave had been dug too small for the coffin. With the large number of miners present, the problem was swiftly rectified.

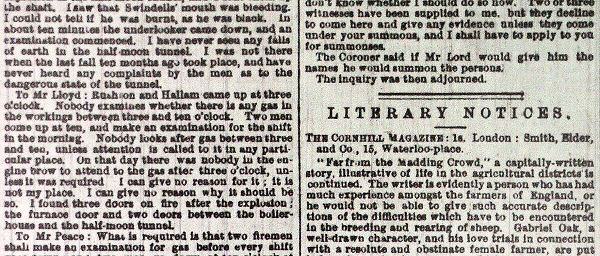

The jury were unable to determine who was responsible. The cavity had at first been filled, but the filling had fallen out and not been replaced. Instead the entrance had been bricked up. The jury tried to discover who had caused the entrance to be bricked, but no-one would admit responsibility. The work had been done some years previously. No firm evidence could be found.

The jury criticised three people. Benjamin ASHTON, the pit owner, for (earlier) employing incompetent managers, and for meddling in the day to day management of the pit. Mr WALSHAW, pit manager when the cavity was bricked, who either gave the order or should have known about it. And David HOLMES, pit underlooker for the whole period, who knew about the cavity and its potentially fatal consequences, but who failed to tell the current highly professional pit manager, who learned about the cavity only after the explosion.

Before closing the inquest the coroner praised all those who went down the pit after the explosion. "He had witnessed their exertions and saw the dangers they were exposed to." There were many, but he particularly singled out messrs HOLT, SIXSMITH and RADCLIFFE. "They were literally soaked with water, and no sooner did they come up and take a little refreshment than they went down again, as if the lives of their own brothers depended on them."

The relatively comfortable and safe lives of those who now live in Dukinfield are built on such foundations.

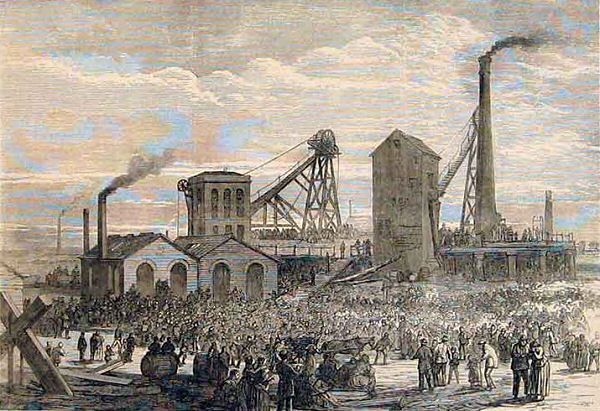

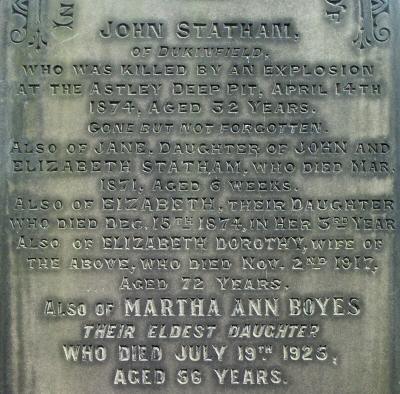

This image and one above courtesy of Tameside Local Studies and Archives Unit